Haiti, the Agony and the Ecstasy

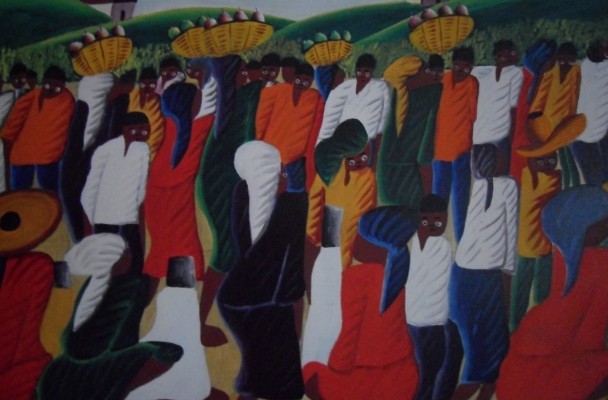

A Haitien Market by Casimir

“Viva la difference” was Haiti’s national slogan for many years. But this land is not simply different from other places, it’s like no other place in the world.

Cloaked in magic, masterfully creative, and miraculously resilient, Haiti is French and seductive in her appearance; African and mysterious in her soul; warm and beguilingly Caribbean in her heart. She is vivid, spicy, heady.

Do not think of her as a resort island in the Caribbean but as a nation whose people – for better or for worse – have been their own masters longer than any country in the Caribbean and whose culture is the most distinctive in the region. Indeed, Haiti’s culture is so fascinating, it overshadows her other attractions. It captivated me from the outset.

In the early 1970’s, a few months after I joined Travel Weekly, I took my first trip to Haiti – and to the Caribbean. It was the beginning of my love affair with both. My publisher, who had had a long relationship with Haiti and had already read the handwriting on the wall regarding Papa Doc, was furious with my editor for letting me go. He did not want me to write about my trip, but I did.

Haiti’s impact on me was immediate and indelible. To this day, I can close my eyes and see the tall, slender woman walking down the mountain road from Kenscoff, balancing a mountain of huge straw baskets on her head with the ease and grace of a ballet dancer. The sight stopped me in my tracks and I watched her continue down the steep road, until she faded from view.

On the road to Jacmel, we stopped at a stand where a market woman was hawking sneakers. She had each pair tied together and her entire inventory rested on her head. Her friend, with whom she was carrying on an animated conversation in Creole, had her goods – six cackling white hens – in a large wash-pan, resting on her head, too.

After a few days, I got up the courage to ride in one of the brightly painted tap-taps, flatbed trucks converted into buses, which careen about town and the countryside at heart-stopping speeds, packed with people and their goods. I was met with great curiosity by a sea of smiling faces.

Haiti explodes with color. Most every street corner of Port-au-Prince has an artist displaying his canvases. One of my first stops was the Cathedral Ste-Trinite to see the extraordinary murals painted by eight of the early artists whose work in the 1950’s brought Haitian art international acclaim.

Among the calamities that resulted from the earthquake that hit Haiti in 2010, one of the greatest was the destruction of the Cathedral and its magnificent paintings.

In the beginning my untrained eye had trouble discerning a master from a budding genius. I bought what I liked. The paintings still hang in my home, giving me as much pleasure now as when I acquired them over three decades ago.

With more familiarity, I came to see that Haitian paintings – colorful and primitive to the casual observer – are a tapestry of Haitian life, reflecting the vibrant colors one sees in the flowers and fruits on the trees, in women’s dresses, on brightly painted buses, in churches, at Carnival, and in the tango of houses from Cap Haitien in the north to Jacmel in the south.

Rhythm, song, and dance are as much a part of Haitian life as color. You need only watch the children on their way to school, by the roadside, in the market; they seem to dance rather than walk. Little wonder that dancers like Katherine Dunham got their greatest inspiration here or that serious students of Caribbean music still go to Haiti to find its roots.

As I learned more about Haiti, I came to understand that all the arts here have meanings lost on outsiders who are unfamiliar with Haiti’s history, particularly regarding the role of voodoo in the evolution of her culture. Like most foreigners, I knew nothing about voodoo and thought it was some sort of black magic, hocus-pocus, or at best, an unusual but unconvincing nightclub act.

But for Haitians, particularly the poor, uneducated majority, voodoo is an all-consuming part of their lives. Nor does Haiti’s educated elite reject it totally, even when they shun it outwardly. As a popular saying reflects, “Haiti is 99 percent Catholic and 100 percent voodoo.”

Haiti has had a brutalizing history. Nothing about it should have produced its remarkable people – joyous with an extraordinary capacity for love and grace in the face of the worst adversity. This indomitable spirit, which manifests itself in every aspect of Haitian life, has been called the soul of Haiti. I would like to believe Haiti’s long agony is over. Yet, I wait and worry as anyone might over a lover or a friend.

© by Kay Showker

Leave a Reply